UTEP Social Work Students Learn Through Show of Hands

Last Updated on May 08, 2017 at 12:00 AM

Originally published May 08, 2017

By Daniel Perez

UTEP Communications

Shannon was proud and young, but knew to seek help when needed. The community college student recently learned she was pregnant and visited the Mesa Street Clinic to learn about how she could enroll in childbirth and parenting classes.

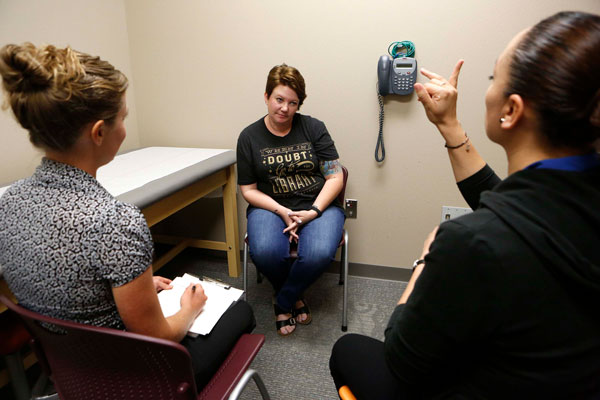

The 20-something woman met with Rob Fernandez, a social work graduate student from UTEP, who assured his client that he would connect her with as many social services as possible to help her. She sat in a metal chair in one of the clinic’s sterile exam rooms and dutifully responded to Fernandez’s questions. Each answer gave the social work student a better picture of what Shannon needed, whether it was services from the Children’s Health Insurance Program or the Women, Infants, and Children food nutrition service.

Fernandez, clipboard in hand, focused on Shannon and refused to be distracted by the person seated to his right who was interpreting every word that Shannon shared through American Sign Language. The use of an interpreter is a different experience for Fernandez, one of about 12 Master of Social Work students who participated in two recent live-action sessions in UTEP’s Simulation Lab.

The sessions were part of a three-year, $800,000 Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) grant to increase the cultural awareness of social work practitioners who enter the behavioral health workforce to assist children, adolescents and transitioning youth in the El Paso region. These particular sessions added client actors who are deaf. Past sessions have focused on dealing with Spanish-speaking clients.

“We want our graduates to be skilled and culturally competent to better serve their clients,” said Kathryn Schmidt, Ph.D., assistant professor of social work and a co-principal investigator of the HRSA grant. She was among the faculty overseeing the simulation. “The focus is on how language – even body language – impacts the service you provide. Sometimes mannerisms can make someone feel unsafe or unwelcome.”

About 25 minutes into Shannon’s interview, an authoritative female voice on an intercom alerted the players that the taped session had ended. “Shannon” relaxed and began to share her observations with Fernandez. Shannon was portrayed by Jennifer Dahlgren-Richardson, deafness resource specialist with the Volar Center for Independent Living in El Paso.

The students met with Dahlgren-Richardson in March in preparation for the simulated sessions in the fictitious Mesa Street Clinic, part of the expansive Simulation Lab on the ground floor of The University of Texas at El Paso’s Health Sciences and Nursing Building. Among the topics were how best to communicate with people who are deaf. The most important pieces of advice were to use direct questions and refrain from abstract terms about feelings.

Dahlgren-Richardson said social workers often deal with people in crisis. The best way pre-service counselors can prepare themselves for the job is to work through their fears, including working with interpreters.

“When you know better, you do better,” Dahlgren-Richardson said during a break after several simulations.

The Census Bureau’s 2015 American Community Survey estimated that 33,774 non-institutionalized people in El Paso County were deaf or had partial hearing loss. Dahlgren-Richardson said El Paso has an active deaf community of about 300.

Candyce Berger, Ph.D., chair and professor of social work, talked about the value of the simulated sessions, especially with new wrinkles such as the use of sign-language interpreters, to better prepare graduates for what awaits them.

“What they learn from a negative experience often is many times stronger than what they learn from a positive experience,” said Berger, a co-principal investigator of the HRSA grant with Alma R. Armendariz, clinical instructor and coordinator of field education.

Fernandez, a Los Angeles native and first-generation college student, spent one year as an intern with UTEP’s Center for Accommodations and Support Services, where he helped students with visible and invisible disabilities take exams and have access to accessible classrooms. He said he interacted with students who were partially deaf during his internship, but those experiences did not help him during the recent simulation.

“I was nervous, but I put my nerves to the side,” Fernandez said before being debriefed by Berger, Armendariz and Dahlgren-Richardson. “My main goal when I walked in that room was to help my client. I knew I could help her.”

Hector Flores, CASS manager of ASL services, said one of his interpreters also participated in the recent simulations. He said this interaction should raise the student’s level of sensitivity.

“If everything is done correctly, it is as if the interpreter is not even there,” said Flores, a working Texas certified interpreter since 1996 who has several family members with different degrees of deafness. “It supports people who are deaf or hard of hearing and provides them with equal access.”