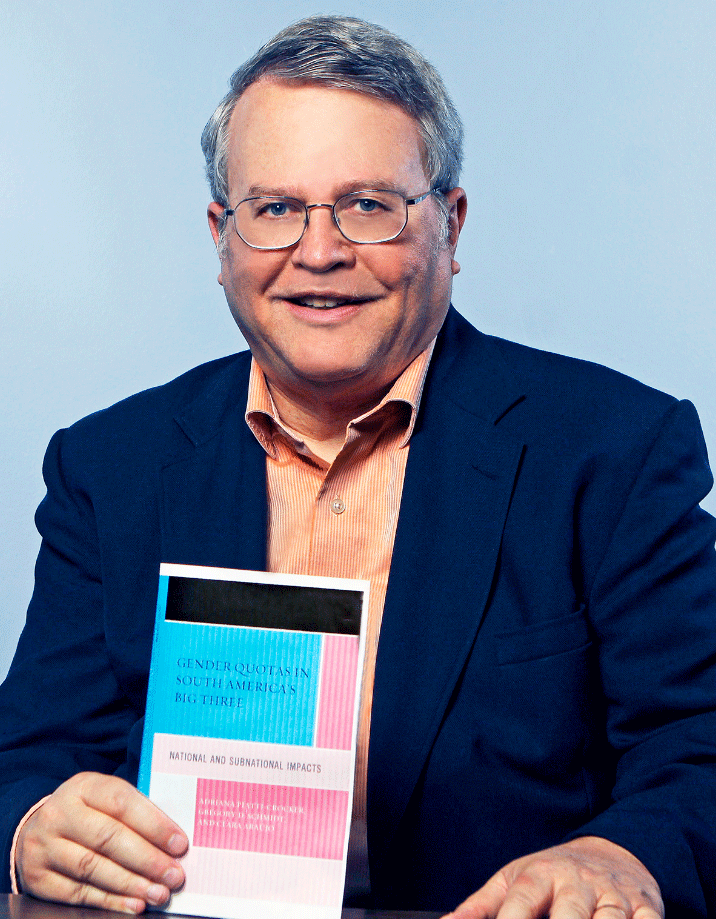

UTEP Professor’s New Book Focuses on Gender Quotas in Latin American Politics

Last Updated on July 24, 2017 at 12:00 AM

Originally published July 24, 2017

By Laura L. Acosta

UTEP Communications

After succeeding her husband as president of Argentina in 1974, Isabel Perón became the first woman president in Latin America.

Since then, seven other Latin American countries – Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Panama – have been led by female presidents. That is the most of any region of the world. Despite being entrenched in a culture of machismo, Latin America has made great strides toward gender balance in government by requiring that a certain percentage of candidates for elected offices be women. Since 1991 almost all of the region’s countries have adopted gender quota laws to boost women's representation in government. As a result, women make up more than half of the lower house of Congress in Bolivia and over 40 percent in Mexico. Overall, women comprise a higher proportion of national legislatures in Latin America than in any other major world region. “The success of gender quotas depends on various factors, especially how they interact with other features of the electoral system,” said UTEP Political Science Professor Gregory D. Schmidt, Ph.D. In the new book, “Gender Quotas in South America's Big Three,” Schmidt collaborated with Adriana Piatti-Crocker, Ph.D., of the University of Illinois at Springfield, and Clara Araújo, Ph.D., of Rio de Janerio State University in Brazil, to compare the effects of gender quotas on the election of women in South America’s three largest countries – Argentina, Brazil and Peru. The book features case studies of each country’s quota systems, expands on the literature about the impact of gender quotas, and examines the prospects for the political representation of women in the national and subnational legislatures of those three counties. “Female candidates have fared best in Argentina, where the electoral system guarantees that women will win about a third of the seats,” Schmidt said. “Women are not guaranteed election in Brazil or Peru, but they have done much better in Peru, whose electoral systems and less expensive campaigns favor their success.” Each researcher focused on one country and wrote about its unique experience with gender quotas. Schmidt investigated regional differences in the impact of electoral rules in Peru. Piatti-Crocker explored substantive representation in Argentina. Araújo examined gender and campaign finance in Brazil. Schmidt, former chair of UTEP’s Department of Political Science, has had a long-standing interest in Peru from his first trip there as a foreign exchange student from The University of Texas at Austin in 1973. Through the years, he has published extensively about Peru with a focus on gender, elections, development, decentralization and executive-legislative relations. He teaches face-to-face and online classes on Latin American politics at UTEP, as well as other classes. For the book, Schmidt obtained data from the National Electoral Tribunal and the National Office of Electoral Processes in Peru to analyze the impact of closed and open lists for the election of women. In closed-list systems, voters cast a single vote for a list of candidates from their preferred party, rather than voting for a person from that party. In open-list systems, voters indicate a party preference on their ballot and may also choose one or more candidates from that party’s list of candidates. Peru uses closed lists to choose local councils and open lists to elect its Congress. Previous studies had indicated that women were more likely to be elected through closed list systems, but Schmidt found that in Peru’s capital of Lima, women have done well under either method. “What I found out is that in Lima it doesn’t really matter for women whether lists are open or closed,” Schmidt said. “The culture is more supportive of women in Lima than in the rest of Peru. When the culture is supportive of women, electoral systems do not make much difference. But in the provinces of Peru, the people are still hesitant to vote for women and that’s where women do better in closed-lists systems than open-lists systems.” Brazil is a different story. The country adopted a gender quota law in 1995, but it has done little to increase the number of women elected. Araújo said Brazil’s electoral list and lack of campaign funds for female candidates are two reasons gender quota laws have not been successful. “Brazil has an open list with a very strong intraparty competition,” Araújo said. “It doesn’t matter who or how many women will compose the list. What is important is if they come from some strategic, but elitist places. Secondly, it’s the money. The intraparty competition and the quantity of candidates work together to build an electoral scenario that is unfavorable to women in general and to the outsiders or people without too much money to spend.” Yet, the three authors point out that public opinion in Latin America has increasingly favored the inclusion of women in positons of political power, and that Latin Americans generally disagree with the assertion that men make better political leaders than women. Argentina adopted the world’s first gender quota law in 1991, and legislative quotas quickly spread to other Latin American countries in less than a decade. Piatti-Crocker credited the success of Argentina’s gender quotas to that country’s electoral system. She also analyzed the influence that gender quotas have had on women’s substantive representation in Argentina, which includes the passage of legislation sponsored by female representatives that benefit women at large and the positions that women occupy on legislative committees. “Most scholars seem to agree that the closed-list PR system that Argentina employs, along with medium to large electoral districts at the national level, have been helpful for women’s electoral success,” Piatti-Crocker said. Schmidt said he hoped the book would contribute to the adoption of gender parity laws in Argentina and Peru, which are under discussion in both countries. Under these proposals, the candidates on party lists would alternate between women and men. He currently is doing research on voter fraud in Latin American electoral systems. In May, Schmidt presented a paper in Lima on electoral reform at the 35th International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, the largest professional association in the world for individuals and institutions engaged in the study of Latin America. “The research in this book does show how the devil really is in the details,” Schmidt said. “One must appreciate how electoral rules interact with quotas and other factors, including culture and finance.”